Author Harry Crews is no longer with us.

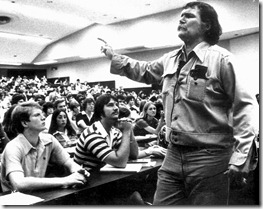

He was an outspoken fellow former Marine, a teacher, a literary mentor to me, and yes, an occasional drinking buddy in Gainesville during my college days of the ‘70s.  He lived what he wrote about, and his verbal tales of his experiences were often far more colorful than his books. He was one of those memorable originals who lived his life to the fullest. We had been out of contact for years when I first learned of his passing through an obituary in the New York Times.

He lived what he wrote about, and his verbal tales of his experiences were often far more colorful than his books. He was one of those memorable originals who lived his life to the fullest. We had been out of contact for years when I first learned of his passing through an obituary in the New York Times.

Harry Crews was a storyteller with a gift for making art of the poverty, brutality, and often bizarre settings of his native South. His raucous novels about derelict but sympathetic folks earned him a special place among the greats of Southern Gothic literature, authors such as William Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor and Erskine Caldwell, to name a few. Early in his career, novelist Norman Mailer commented: "Harry Crews has a talent all his own. He begins where James Dickey (the author of Deliverance) left off." But Harry’s characters were always his own.

He wrote plays, essays, short stories, and novels. He wrote about Georgia rattlesnake rodeos, midgets, traveling evangelists, violent alcoholics and even depicted a man who ate an entire Ford Maverick… a few ounces at a time. But all along he demonstrated a true empathy for his broken down characters, many of whom had just been trying to escape from the hardships of their bitter lives.

Just like his fictional characters, Harry Crews lived a rough life. As a youngster he was often laid up with an undiagnosed infirmity that caused paralysis and spasms, which prompting visits from faith healers. Around age six he fell into a tub of boiling water used to skin butchered hogs. Stories became his refuge amid the poverty of his youth “in the worst hookworm and rickets part of Georgia.” His mother’s second, turbulent marriage and divorce from a drunken uncle whom Crews had been led to believe was his natural father; shuttled back and forth as his mother tried to raise he and an older brother, earning a living in a factory ghetto of Jacksonville, Florida… these and other experiences would feed his desire to imagine, to create and, ultimately, to write. He served three years in the Marine Corps, and on the G.I. Bill he studied at the University of Florida with novelist Andrew Lytle, who profoundly influenced his writing. He and his wife, Sally, married and divorced twice. One of their sons, Patrick, drowned in a neighbor’s pool at age 4.

Harry’s first novel, The Gospel Singer, was the one that came to wide notice. Published in 1968, this book about a traveling evangelist who meets a vivid fate in a Georgia town introduced us to characters of the type that would occupy his later novels: sideshow freaks, a runaway lunatic and a sociopath or two. It was the first of his books that I had read, even before I later met him in Gainesville. And it was his book A Feast of Snakes (1976) which concerns a Georgia town’s obsessive fixation on their annual rattlesnake rodeo that is considered by many to be his finest novel, and it’s still a personal favorite.

Harry’s first novel, The Gospel Singer, was the one that came to wide notice. Published in 1968, this book about a traveling evangelist who meets a vivid fate in a Georgia town introduced us to characters of the type that would occupy his later novels: sideshow freaks, a runaway lunatic and a sociopath or two. It was the first of his books that I had read, even before I later met him in Gainesville. And it was his book A Feast of Snakes (1976) which concerns a Georgia town’s obsessive fixation on their annual rattlesnake rodeo that is considered by many to be his finest novel, and it’s still a personal favorite.

His 1978 memoir, A Childhood: The Biography of a Place, was a masterpiece in which Harry wrote about his birthplace, a sharecropper’s cabin at the end of a dirt road, paying homage to rural South Georgia, "all its loveliness and all its ugliness."

“I first became fascinated with the Sears catalogue because all the people in its pages were perfect. Nearly everybody I knew had something missing, a finger cut off, a toe split, an ear half-chewed away, an eye clouded with blindness from a glancing fence staple. And if they didn’t have something missing, they were carrying scars from barbed wire, or knives, or fishhooks. But the people in the catalogue had no such hurts. They were not only whole, had all their arms and legs and eyes on their unscarred bodies, but they were also beautiful.”

― Harry Crews, A Childhood: The Biography of a Place

A decade characterized by drug and alcohol abuse and creative lapses ended in 1987 with the publication of his ninth novel, All We Need of Hell. He loved drinking, which I witnessed during those days in Gainesville… and it almost killed him. He had his share of fist-fights and arrests in small-town bars; I never witnessed them, but heard of the local legends about it. He once awoke from a bender in Alaska with a tattoo of a hinge stamped in the bend of his right elbow. His writing slowed down until he got sober in the late 1980s.

Over the years, Harry also penned stories for magazines such as Playboy, and he wrote a column called "Grits" for Esquire, covering Southern rural topics as dog fighting, cockfighting contests and gator poaching. Before retiring in the ‘90s, he had taught writing for many years at the University of Florida in Gainesville.

Published abroad in the U.K. since 1972, Harry’s works have been translated into Dutch, Italian, French, Basque, Hebrew, and German. In 2002, the University of Georgia Libraries honored Harry for his literary output, inducting him into the library’s Georgia Writers Hall of Fame, and his extensive files of papers were acquired by the Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library of the University of Georgia in August 2006. In 2009 the Florida Arts Council inducted him into the Florida Artists Hall of Fame.

Harry played a brief role in Sean Penn’s 1991 film The Indian Runner and dedicated his book Scar Lover to Penn. In 2007, a documentary was released by filmmaker Tyler Turkle: Harry Crews – Survival is Triumph Enough. The personal format is loosely based on an interview, and the themes explored include hardship, tragedy and loss throughout the Crews’ life.

After a long illness caused in part by a couple motorcycle accidents, Harry Crews died at 76 on March 28th at his home in Gainesville, the town that had been his home for over 40 years. He is survived by his ex-wife Sally Ellis Crews; his son, Byron Jason Crews, who teaches English at Wright State University; and a grandson. Per his wishes, there was to be no service. At the time of his death it’s said that he was at work on a novel set in the 1940s in the Springfield Section of Jacksonville, Florida.

After a long illness caused in part by a couple motorcycle accidents, Harry Crews died at 76 on March 28th at his home in Gainesville, the town that had been his home for over 40 years. He is survived by his ex-wife Sally Ellis Crews; his son, Byron Jason Crews, who teaches English at Wright State University; and a grandson. Per his wishes, there was to be no service. At the time of his death it’s said that he was at work on a novel set in the 1940s in the Springfield Section of Jacksonville, Florida.

On March 29th, Dwight Garner said it well in the New York Times:

The literary world needs its outsiders and outlaws, now more than ever, and with Mr. Crews’s passing there are very, very few of them left.

And what did I learn from Harry during those days in Gainesville? He said it was a writer’s duty to “get naked, to hide nothing, to look away from nothing… to not blink, to not be embarrassed by it or ashamed of it. Strip it down and let’s get to where the blood is, where the bone is.”

It was a recurring theme that he told his students, and one time he looked me straight in the eyes, telling me to write it down and said:

“If you’re gonna write, for God in heaven’s sake, try to get naked. Try to write the truth. Try to get underneath all the sham, all the excuses, all the lies that you’ve been told.”

Harry is gone, but not forgotten. His words still ring true.